Animals that reproduce once a year during a short breeding season need to get the timing right. Breed too early and the offspring might be exposed to harsh conditions, breed too late and the offspring might not be able to grow enough to survive the first winter. Generally, one of the major factors determining the timing of breeding is the environment. Therefore, due to climate change, we can expect shifts in the timing of breeding and indeed, various studies show that a shift towards earlier breeding in many animal species can be observed globally. This applies also to amphibian species, but in their case, not much is known about populations living at high elevations. We decided to fill this knowledge gap by looking at how the timing of breeding has shifted in the past 40 years in a population of common toads (Bufo bufo) which lives at almost 2000 masl in the Swiss Alps, just below the Grosse Scheidegg (Figure 1). We expect temperatures and amount of snow cover to play an important role. In fact, only once the snow melts and the breeding pond unfreezes can the toads emerge from hibernation belowground and successfully breed.

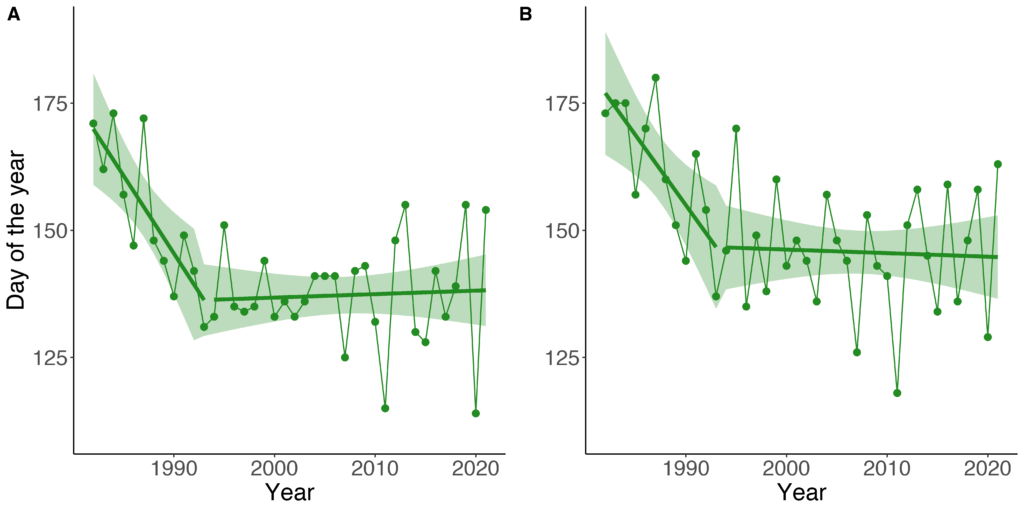

Our results matched our expectations. We found that the warm temperatures and low amount of snow in winter and spring were associated with an earlier breeding. Interestingly, both temperature and snow cover have not been changing necessarily as expected over the past forty years at our study site. We observe great year to year variability, and to this day we can observe both late breeding (mid-late June) and early breeding (late April). Despite this great variability, breeding on average occurs earlier than in the 1980s (Figure 2), with an advancement of about 30 days. Further details and information can be found in our article “Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers” published in the diamond Open-Access Peer Community Journal (doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.240)