“Thank you”, I whispered in a soft voice while driving by the rayon and plating factories surrounding Lake Orta. “Thank you for giving me a PhD”.

The wastewater of those factories polluted the lake with copper and ammonium sulphate from approaching the mid-nineteen hundreds until the end of the last century. This history of pollution makes Lake Orta an interesting ecosystem to study, and sets the perfect stage for my PhD: the life-history responses of the rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus to past environmental changes (i.e. industrial pollution) and the underlying eco-evolutionary processes.

To study this, I (try to) resurrect rotifers from up to 80 year old lake sediments that contain their resting eggs, and compare the performance of these rotifers under different experimental treatments. As I have had some difficulties getting resting eggs from the post-pollution conditions, I decided to go to Lake Orta to get the most recent Brachionus calyciflorus: the ones that are currently swimming around.

Together with Diego Fontaneto of the ‘Istituto per lo Studio degli Ecosistemi’, I drove around the lake, and found five spots to easily enter the lake to collect zooplankton with a plankton net. This net made of fine nylon mesh is pulled through the water horizontally and the animals are captured in a vial at the bottom of the net.

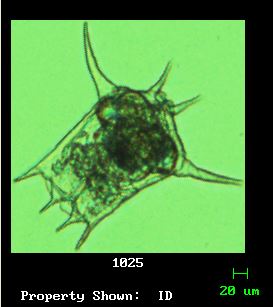

A quick look together with Diego revealed that we captured tons of animals, but probably no Brachionus. A more thorough look together with our summer research assistant Conor Waldock confirmed this suspicion, but we have still some bottles of water to go through, so we keep on hoping. And otherwise, our hope lies in the sediment samples of Lake Orta that I also brought back from the trip.

The reason why we didn’t find any Brachionus in our water samples? Probably because the water was still too cold due to the relatively bad summer, and there have been no big algae blooms yet of which Brachionus could profit. I guess this means I have to go back next month to again sample Italian ice cream… Ehm, Lake Orta I mean.